Inside a Collection of ‘Imaginary’ Books

Fictive art, Byers tells the class, helps “raise awareness in the observer that not everything they read is real.” It’s a particularly timely reminder, as fake AI-generated book titles spread across the web, and creep onto real citation lists across disciplines.

It’s a checklist of joke publication titles made perfectly three-dimensional– and Byers loves resting in the space, watching visitors obtain the joke in real time. “That’s how I understand I obtained them– and they obtain it.”

Creating fictive art is a delicate procedure. “The factor of reveal is the key on which this kind of art runs,” Byers informs me. You desire to make the visitor, as it were, obtain it quickly enough that they feel they’re part of it.”

Yet it’s in the theatrical that the world encounters these publications– and with any luck obtains the joke. Each private book is a delight, yet the presentation of them all in the gallery– teeming with Byers’s own wry personality as “manager”– are what absolutely offer the principle.

Composing imaginary books is “a light-weight pastime,” Byers explains to the class, one you could do totally in your head: you can think up fictional book titles in a dental expert’s waiting space, he recommends, or while you’re on jury task.

There is, of course, an expensive distance between those randomly produced hallucinations and Byers’s wayward– and purposefully phony– collection of publications. The event is a testament to centuries of human imagination, in addition to the power that lies in the liminal area between our creative imaginations and truth.

Surrounded by the sturdy-looking devices of bookbinding– large sheets of paper, a pegboard of hammers, a row of heavy publication presses lining the windowsill– it’s easy to really feel grounded in the materiality of the tool. Yet on the projector display, a slide checks out, “Gathering the imaginary.”

Back at the Center for Publication Arts, Byers advises the course in this component of efficiency. He breaks down the collection-creation procedure right into 3 tasks: the literary, the artistic, and the theatrical. The literary task is fertilization: composing titles and their backstories, also resembling actual catalogue listings. The imaginative part is, in his words, “the fun task”: there’s a vast array of approaches he utilized to literally develop these objects. (While he made a lot of the books himself, typically by means of really budget-friendly methods, some were constructed or finished by knowledgeable artisans.).

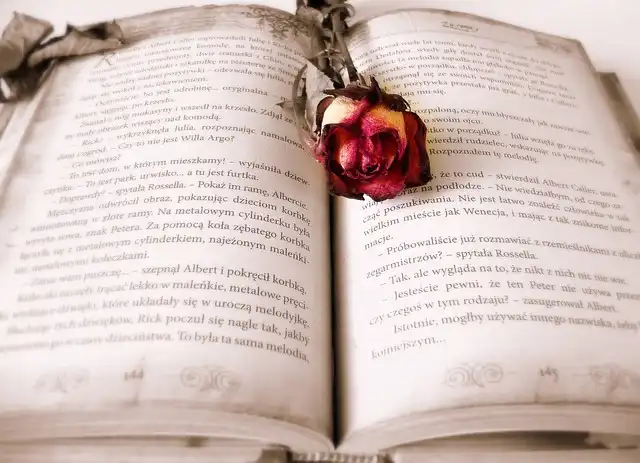

Sitting beside the appreciable shelves on the second flooring of the Grolier Club, Byers’s own imaginary books feel really actual– and unbelievable. “The dimensionality and the weight of the publications provides them a touch of unreality that is various from a checklist of fictional publications,” Byers informs me. In his publication, Byers talks about checking out C. S. Lewis’s Voyage of the Dawn Treader as a youngster, and viewing Lucy Pevensie run into the Magic Book. Byers’s collection is completely devoted to books discussed in other (real) publications. It’s a checklist of joke book titles made beautifully three-dimensional– and Byers likes resting in the space, seeing site visitors obtain the joke in real time.

Fictive art, Byers informs the course, helps “elevate awareness in the viewer that not every little thing they review is genuine.” It’s a specifically timely pointer, as phony AI-generated book titles spread throughout the web, and creep onto actual citation checklists across techniques.

And then there are the “fictive”: publications that are “actual” in fictional worlds, one metatextual layer on top of another. While the other categories will delight fans of literary background, the fictive touches a particularly fannish area, like seeing a remarkably realized cosplay of a personality that formerly just existed on the web page.

Fictional book collecting has a rich and lengthy literary background– particularly when it comes to humor. In the 19th and 18th centuries, slaves’ flows in affluent households were commonly hidden by “jib doors,” bookshelves constructed directly right into wall surfaces, and some of the extra humorous-minded would put phony titles on the phony books.

Byers’s collection is wholly dedicated to publications stated in other (genuine) books. He’s split them into three groups: the shed, the incomplete, and the fictive. Amongst the lost are Byron’s memoirs, burned on his orders by his author, and Hemingway’s very first novel, swiped from a train carriage a century later on. The unfinished consist of the “deserted,” the “uncertain,” also the “endangered”: Sylvia Plath’s “strangely disappeared” semi-autobiographical unique Dual Exposure, or Raymond Chandler’s Shakespeare in Child Talk. “Of certain interest,” the exhibition card notes, “is the essay on As Ums Wikes It.”

Like his fellow Grolier members, Byers shares a deep interest in books as physical objects. In his newest book, a remarkable– and fittingly dry– friend to the collection of the very same name, he opens with a quote from English humorist Max Beerbohm, regarding the fictional titles he ‘d created. “I long for– it might be a foolish impulse, but I do yearn for– ocular proof for my belief that those publications were created and were published,” created Beerbohm. “I intend to see them all varied along goodly shelves.”

Sitting close to the substantial shelves on the 2nd flooring of the Grolier Club, Byers’s very own fictional publications really feel very genuine– and unbelievable. “The dimensionality and the weight of the books provides a touch of unreality that is various from a checklist of fictional publications,” Byers informs me. “It makes both the need and the illusion rise.” Visitors of swashbuckling nautical books might identify the copy of Stephen Maturin’s Thoughts on the Avoidance of Diseases Most Typical Among Seamen. Beyond of the room is a purple-covered copy of The Tracks of the Jabberwock– among the initial things Alice experiences when she experiences the looking-glass, its title printed backwards, much like guide she sees.

In his book, Byers speaks regarding reviewing C. S. Lewis’s Voyage of the Dawn Treader as a child, and watching Lucy Pevensie encounter the Magic Publication. Making physical variations of pretend publications, many made with flawlessly selected and occasionally amazingly convincing information, enhances that desire: you can look, however you can not review.

1 book presses lining2 books

3 heavy book presses

« Hardscrabble, DelawareJack Kerouac Alley »